John Garth

A salutary lesson in his youth taught Tolkien that fairy-stories are not only or mainly for children. Here I uncover the who, the where and the when. Voted best article in the inaugural Tolkien Society Awards, 2014.

Published here in 2013, this is a slightly edited version of one that appeared in Tolkien Studies 7, 2010.

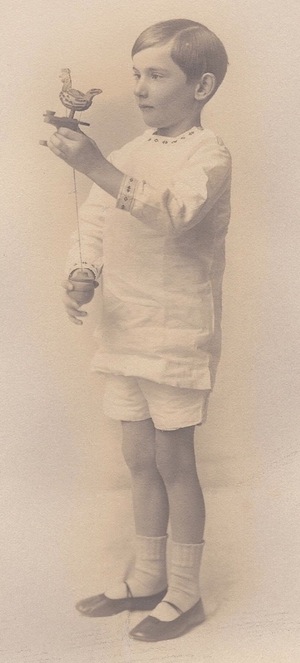

Hugh Cary Gilson at eight years old

Hugh Cary Gilson at eight years oldThe manuscripts of Tolkien’s deeply influential lecture ‘On Fairy-stories’ include a striking anecdote in which that great proponent of Faërie, the author, recalls being put in his place by a small, thoroughly scientifically-minded boy. It is an entertaining little nugget, but I would suggest that it is more than that: it identifies a moment in the author’s life which encapsulated for him, even some thirty years later, the defining idea behind his legendarium: that fairy-stories are not solely or primarily for children. Here I not only reveal the identity of the boy, but also provide photographs of both child and garden, while offering some thoughts on the date of the incident.

The anecdote appears among the pages written by J.R.R. Tolkien when he was revising and enlarging his original 1939 Andrew Lang lecture for publication in Essays Presented to Charles Williams, published in 1947. However, the passage itself was excised by the author and leaves no direct trace in ‘On Fairy-stories’. It finally appeared in 2008 in Tolkien On Fairy-stories, edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson, which includes Tolkien’s fascinating and extensive drafts of the lecture.

Tolkien introduces the incident to illustrate why the fairy-story should not be specially tailored for children in either tone or content. ‘Do not let us write only for them, certainly not “down” to them,’ he warns: children old enough to enjoy a fairy-story are already old enough to know when they are being patronised. ‘Children prefer adult conversation – when it is not infantile in all but idiom. But being talked down to (even in verbal idiom) is a flavour that they perceive quicker than any “grown-up”...’

Tolkien describes the encounter as a ‘salutary lesson’:

I was walking in a garden with a small child. I was only nineteen or twenty myself. By some aberration of shyness, groping for a topic like a man in heavy boots in a strange drawing room, as we passed a tall poppy half-opened, I said like a fool: ‘Who lives in that flower?’ Sheer insincerity on my part. ‘No one,’ replied the child. ‘There are Stamens and a Pistil in there.’ He would have liked to tell me more about it, but my obvious and quite unnecessary surprise had shown too plainly that I was stupid so he did not bother and walked away.

Tolkien gives no hints regarding the location of the garden, and few about the identity of the young sceptic. Indeed there is little here, beyond faith in Tolkien’s veracity, to indicate that the incident is more than a concoction to enliven his essay. However, he does recollect the boy’s age – ‘five was young for such good sense’ – and adds: ‘The child certainly later became a botanist.’1

Friends: Robert Quilter Gilson (left) and Tolkien in 1910 or 1911

Friends: Robert Quilter Gilson (left) and Tolkien in 1910 or 1911In fact the anecdote was perfectly true, and the child was Hugh Cary Gilson, half-brother of Tolkien’s schoolfriend Robert Quilter Gilson. Rob was a vital figure in Tolkien’s life: one of the close circle of friends who called themselves the T.C.B.S. and who became the first readers of his nascent mythology. Rob and Hugh’s father was Robert Cary Gilson, headmaster of King Edward’s School, Birmingham, who had remarried two years after his first wife’s death in 1907. The garden belonged to the Gilsons’ home, Canterbury House, which stood in the village of Marston Green a few miles outside the city.2

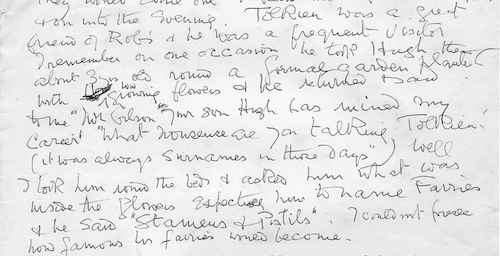

I know all this because Hugh’s mother Marianne Caroline Gilson – the headmaster’s second wife and Rob’s stepmother – tells the same story in an unpublished memoir she wrote in her nineties:

Tolkien was a great friend of Rob’s and he was a frequent visitor. I remember on one occasion he took Hugh, then about 3 years old, round a formal garden planted with low growing flowers and he returned and said to me, ‘Mrs Gilson, your son Hugh has ruined my career’ – ‘What nonsense are you talking, Tolkien?’ (It was always surnames in those days.) ‘Well, I took him round the beds and I asked him what was inside the flowers expecting him to name Fairies and he said, “Stamens and Pistils.”’ I couldn’t foresee how famous his fairies would become.3

The encounter as told by Marianne Gilson in her memoir, written in 1969 or later

When I first saw Mrs Gilson’s memoir, before I read Tolkien On Fairy-stories, I was inclined to suspect the story had arisen after Tolkien became famous for his fairies. Now, with two independent witnesses, it can be taken as confirmed.

It turns out that J.R.R. Tolkien also told this story to at least one other person – his son Christopher, who has told me:

I have a perfectly clear ‘snapshot’ memory of my father telling me this story – and not a memory suddenly stirred from long hiding, but a permanent recollection of him. He gave me of course no indication of who the supercilious child was, but I have never forgotten his saying ‘Stamens and Pistils’ with a scornful puckering of his features to express the contempt in the boy’s voice. I don’t know when this was, but I was certainly still fairly young, and I’m fairly sure that it would have been in the period 1938-40, when owing to illness I was not at school and we often went about together on botanical expeditions.4

The date as recollected by Christopher Tolkien is, of course, close to the period when his father would have written the anecdote down for use in his expanded version of ‘On Fairy-stories’.

When the exchange took place is far less clear, and here Tolkien’s recollection may seem less reliable than Marianne Gilson’s. Hugh was born on 3 June, 1910: if Tolkien had indeed been 19 or 20, the year would have been 1911 or 1912, and even the most precocious child would surely not be talking about stamens and pistils at one or barely two years old.

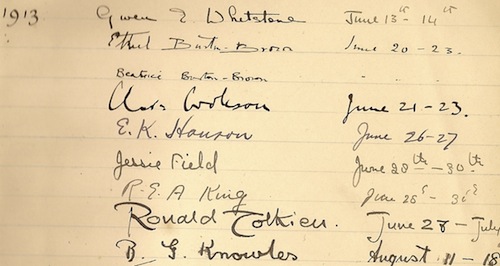

Tolkien’s record of his stay from June 28 to July 1, 1913, in the Canterbury House visitors book

On the other hand, if Hugh were five the First World War comes into the equation. In 1915 Rob was away on military training and from early the next year he was on the Western Front, where he was killed in battle on 1 July, 1916. He was on leave at Marston Green on Saturday 17 July, 1915; Tolkien was in the Birmingham area and may have taken the opportunity to see him before his own military training started on the Monday.5 The two seem to have seen each other only once more, at the T.C.B.S. ‘Council of Lichfield’ in September 1915; Rob invited the gang to Marston Green but even if they went, would poppies have been in flower so late?6

On the face of it, therefore, the visit seems more likely to have taken place in 1913 or 1914, when Tolkien and Rob had more leisure to see each other and Hugh was three – as his mother recalled – or had just turned four. We know that Tolkien proposed to visit Marston Green on 14 June, 1913, and his signature in the visitors book for Canterbury House confirms that he also made a longer stay from 28 June to 1 July.7 But there may have been other visits for which we have no record: Tolkien was ‘a frequent visitor’ and seems only to have signed when he stayed overnight.

As an indication of Hugh’s intellectual development at this stage, a March 1913 letter from his father to his mother is eye-opening:

Hugh and I recite more than 300 lines of ‘Horatius’ every morning. He never seems to tire of it. It is a reflection on my barbarous pronunciation of the proper names that he is inclined to call Aunus (‘of green Tifernum, lord of the hill of vines’) ‘Ornament.’ Somehow proper Italian pronunciation does not seem to suit the Lays of Ancient Rome...8

Precocious: Hugh in Horatian mode with half-brother Rob, 1913

Precocious: Hugh in Horatian mode with half-brother Rob, 1913Knowledge of stamens and pistils at the age of three should not greatly surprise us from a boy who, some months earlier, could already grasp Lord Macaulay’s 1842 narrative poem – even if he mispronounced some of the names. He inherited from his father an amazing capacity for retaining knowledge, and later in his own children’s eyes ‘seemed to know everything’ except music and popular culture.

A final consideration is Mrs Gilson’s remarkable statement that Tolkien said Hugh’s comment had ruined his career. She was writing her account in 1969 or the early 1970s when Tolkien was enormously famous as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, so it would be understandable if her memory had played tricks on her. Surely Tolkien had no more idea than Marianne Gilson in 1913 that Faërie would make his name.

However, it does not seem to me impossible that Tolkien said these words to her, if we accept the later date of summer 1915. Just after the outbreak of war he underwent an astonishing creative awakening and began creating what became Middle-earth, a project which he certainly saw as central to his identity. The great epiphany came with a gathering of the T.C.B.S. in Wandsworth in December 1914, the ‘Council of London’ in which, as he recalled two-and-a-half years later, he first became conscious of ‘the hope and ambitions’ that were to endure with him:

That Council was as you know followed in my own case with my finding a voice for all kinds of pent up things and a tremendous opening up of everything for me.9

Clearly, we cannot press these evidences for dates for absolute certainty. But if we accept that Tolkien spoke of his career being ruined, it lends much weight to the idea that the meeting with Hugh Gilson in the garden of Canterbury House took place in the summer of 1915. Notably, this was the year Tolkien began his first lexicon of Qenya, detailing his ‘Faërie’ world in the tongue he invented for its denizens. So fairies were very much on his mind. What is more, the Qenya lexicon reveals that Tolkien himself had an answer to the question of who might live inside a poppy.

Rob Gilson and Tolkien in 1910 or 1911 with King Edward’s School prefects and headmaster Robert Cary Gilson — to the right of whom sits T.C.B.S. member Christopher Wiseman

In ‘Manuscript B’ of ‘On Fairy-stories’ Tolkien declares that as a child he, like Hugh, ‘was interested also in the structure and particularly in the classification of plants.’ Furthermore, he adds, he ‘never at any age that I can recall had any interest in “fairies” that a frivolous adult fancifulness may put to dwell in them.’10 We are indeed accustomed to think of his Elves as creatures of noble or even superhuman stature, a conscious reaction against the diminutiveness that had dominated the English view of fairies for centuries. Tolkien protests that he personally had never fallen for this fakery, ‘that long line of flower-fairies and fluttering sprites with antennae that I so disliked as a child’.11 In the published essay, Tolkien derides ‘this flower-and-butterfly minuteness’ promoted by William Shakespeare and Michael Drayton, seeing it as ‘a product of “rationalization”, which transformed the glamour of Elfland into mere finesse, and invisibility into a fragility that could hide in a cowslip or shrink behind a blade of grass.’12

The evidence of his own youthful writings, unfortunately, is against him here. The faërian creatures of the 1910 poem ‘Wood-sunshine’, of 1915’s ‘Goblin Feet’ and ‘The Princess Ní ’, and even of the Qenya poem ‘Narqelion’ written in 1915-1916, are all small, flittering, floral or sylvan (though at least they have no antennae). In the opening chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, written in 1917, the mortal wanderer Eriol has to become small to enter the Cottage of Lost Play – though it is clear that Tolkien conceived of the Elvish inhabitants as formerly of greater stature.13 The Qenya lexicon strays unabashedly into Draytonian territory, naming not only Ailinónë, ‘a fairy who dwelt in a lily on a pool’ and Nardi, ‘a flower-fairy’, but also Tetillë, who is described precisely as ‘a fairy who lived in a poppy’.14

Canterbury House, Marston Green, in 1905 with Rob and his sister Molly sitting on the terrace. Below: Their mother Emily (who died in 1907) sits near one of the flower beds

Canterbury House, Marston Green, in 1905 with Rob and his sister Molly sitting on the terrace. Below: Their mother Emily (who died in 1907) sits near one of the flower beds

So Tolkien may, retrospectively, have felt his question to Hugh Gilson to be a mere foolish ‘aberration of shyness’ but at the time (if we accept a 1915 date for the encounter) it was no aberration: it was quite consistent with what he was writing privately. In the next few years his creations did steadily shed the Draytonian baggage of flowery diminutiveness, but even in The Hobbit the Elves of Rivendell fail to rise above mere decorative silliness, and in these early chapters Tolkien continued ‘talking down’ to children. It is only in ‘On Fairy-stories’ that he explicitly rejected such things as faults, and only in The Lord of the Rings (for which the essay may be seen as a manifesto) that he put his views consistently into practice. Judging from the manuscripts now published in Tolkien On Fairy-stories, the memory of a precocious, outspoken boy played its part in the process.

Hugh Gilson, as his obituary in The Independent newspaper noted, was ‘brought up in a disciplined intellectual environment’ at home. He had an extremely organised and practical mind, like his father, who instilled in him an intense interest in how things worked. He later attended Winchester School and then (following in the footsteps of his half-brother Rob) Trinity College, Cambridge, to study Classics. There he switched to Natural Sciences, specialising in Zoology and Comparative Anatomy, and achieved a double First from what seemed to be a standing start.

Hugh, centre, with his younger brother John and their mother

Hugh, centre, with his younger brother John and their motherIn 1937 he led an expedition to Lake Titicaca, high in the Andes, where he collected valuable biological samples and data and formed an enduring interest in freshwater lakes. Returning to Cambridge he taught Zoology, where the clarity of his lectures was remarkable (‘he made even the torsion of gastropods seem simple,’ one student recalled) and during the Second World War he ran a unit producing freeze-dried plasma for the Royal Navy. From 1946 to 1973 he was the director of the Freshwater Biological Association near Bowness on Lake Windermere, greatly expanding its reach and effectiveness. But he was no desk-bound manager: he spent much of his time in the FBA workshops helping to design many of the instruments and other items of equipment used for collecting specimens and conducting experiments. At home, too, he had a large workshop with a lathe and a veritable treasure trove of other tools and equipment. He loved a challenge and would make or mend things for friends and family – particularly clocks. In 1970 he was awarded the CBE, as Tolkien was in 1972. He gives his name to the Hugh Cary Gilson Award, an annual prize of £4,000 given to a member of the FBA to assist with original freshwater research.15

Colleagues and students admired him but knew that he did not suffer fools gladly. In his ‘On Fairy-stories’ draft, Tolkien writes as if the boy in the garden typified a child’s attitude to being spoken ‘down to’ about fairies. But in his scientific precocity, and the shyness and impatience that went with it, the young Hugh Gilson was far from typical. In the words of his obituarist, ‘He was often forthright, and at times tactless...’ His daughter Julia Margretts says that, although he mellowed with age, he hated being wrong (and rarely was). She recalls of her own childhood: ‘Sometimes we wanted the ground to swallow us up when he was making a point – he could in fact be more than tactless and was, on the odd occasion, even rude.’ When Hugh stumped off through the garden in Marston Green, it seems that Tolkien may have escaped lightly.

• If you have enjoyed this article, please consider a donation to help pay for physiotherapy and equipment for Charlie Grainger, who has cerebral palsy.

Note and acknowledgments

This small glimpse into Tolkien’s life is particularly satisfying for me, because it was Hugh Cary Gilson who led me to the Gilson family, albeit posthumously. In May 2000, I had for months been trying to make headway with biographical research for my book, Tolkien and the Great War, and felt I was banging my head against a brick wall – especially in regard to tracing living relatives of members of the T.C.B.S. But then I chanced to look up ‘Cary Gilson’ in a digital newspaper archive, hoping for some reference to the headmaster of King Edward’s School, and discovered instead his botanist son – and the Freshwater Biological Association. Sadly he had died just a few months earlier. The FBA put me in touch with Hugh Gilson’s family, who had not only preserved Rob’s letters but were willing to let me examine them thoroughly, greatly enhancing my account of the T.C.B.S.

I would like to thank Hugh Cary Gilson’s daughter Julia Margretts for allowing me to examine her grandmother’s memoir, for scanning family photographs for publication when this article first appeared in Tolkien Studies, and for providing a fascinating portrait of her father, from which I have quoted freely. I am grateful to her extended family for once again allowing me to publish details from their family history. I am also grateful to Christopher Tolkien for kindly volunteering his own recollection of his father’s anecdote and allowing me to include it here. R.Q. Gilson’s letter to J.R.R. Tolkien on 13 June, 1913, is cited with the permission of the Tolkien Estate. And I thank David Doughan for drawing my attention to Tolkien’s version of the flower-garden incident.

Finally, I’d like to thank members of the Tolkien Society who voted this as best article in their 2014 awards (and voted one of my more recent pieces featuring Rob Gilson, ‘Tolkien’s “immortal four” meet for the last time’, best article in the 2016 awards).

Explanatory notes

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, Tolkien On Fairy-stories, edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson (London: HarperCollins, 2008), 248.

[2] Now, in a sign of progress that would doubtless have greatly saddened Tolkien, Marston Green is the site of Birmingham International Airport and the surrounding countryside has given way to business parks, housing estates and shopping centres.

[3] ‘Reminiscences of Marianne Caroline Cary Gilson (née Dunstall),’ begun February 1969 (Gilson family papers, private collection; some punctuation added for clarity). Mrs Gilson died in 1977 aged 98.

[4] Christopher Tolkien to the author.

[5] Letter from R.Q. Gilson to Marianne Gilson, July 19, 1915; no reference is made to Tolkien (Gilson family papers).

[6] For the Council of Lichfield, see my book Tolkien and the Great War, 101-2.

[7] Letter from R.Q. Gilson to J.R.R. Tolkien, June 13, 1913 (Tolkien family papers, Bodleian Library). The Canterbury House visitors book shows Tolkien also stayed on December 16-19, 1911, and June 28 to July 1, 1912 (Gilson family papers).

[8] Letter from R.C. Gilson to Marianne Gilson, March 21, 1913 (Gilson family papers).

[9] Letter from J.R.R. Tolkien to Geoffrey Bache Smith, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Humphrey Carpenter (London: HarperCollins, 2006), 10.

[10] Tolkien On Fairy-stories, 248.

[11] Tolkien On Fairy-stories, 29-30.

[12] Tolkien On Fairy-stories, 29.

[13] The Book of Lost Tales, part one, 14.

[14] ‘Qenyaqetsa: The Qenya Phonology and Lexicon,’ edited by Christopher Gilson, Carl F. Hostetter, Patrick Wynne, and Arden R. Smith, Parma Eldalamberon 12 (1998), 29, 68, 92. In The Book of Lost Tales the word ‘fairy’ is used interchangeably of Elves and of nature spirits akin to the Valar. It is impossible to judge whether such a distinction existed when Tolkien made these earlier lexicon entries.

[15] Julia Margretts to the author; David Le Cren, ‘Obituary: Hugh Gilson’, The Independent, February 10, 2000; The Times, October 8, 1935, 16.

© John Garth 2010. Reproduced with thanks to West Virginia University Press. Gilson family photographs reproduced with permission of Julia Margretts.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College