Tolkien fantasy was born in the trenches

John Garth

“He was shipped home with trench fever, his head full of powerful images that were to re-emerge more than two decades on in The Lord of the Rings” “He was shipped home with trench fever, his head full of powerful images that were to re-emerge more than two decades on in The Lord of the Rings” |

This was originally published in the Evening Standard on 13 December 2001 just after the premiere of Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring and a week before the film went on general release. The article sketches some of the ideas underlying Tolkien and the Great War, which I was then writing.

A couple of points to add now: I should have said the hobbits evoke the ordinary men of Tolkien's battalion; and I regret that Jackson's vision of the Dead Men of Dunharrow did not evoke those real-life soldiers at all.

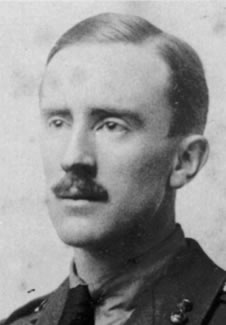

Middle-earth was born in hospital in 1916 when J.R.R. Tolkien was invalided from the Somme with trench fever. He had been in battle twice: early in the campaign in a night attack on a ruined village, and again when a German trench was seized in the cold autumn daylight.

In between he had been made battalion signalling officer and spent long weeks in the trenches where he witnessed all the horrors of mechanised death. But just before his fellow soldiers were moved on to another ordeal at Ypres, Tolkien fell ill and was shipped home with his head full of powerful images that were to re-emerge more than two decades on in his masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings.

Lying in hospital in Birmingham, Tolkien wrote out in an exercise book the haunting epic of Gondolin, a city of high culture which is destroyed in a hammerblow by a nightmarish army. The worst and best of what he had seen in the Somme soldiery were embodied in the brutal goblin attackers and the elvish defenders, valiant against hopeless odds. Among the dragons and demons in the assault are bizarre machine-like monstrosities which hurl fire or from which troops debouch: the archaic prose might be describing a tank — then newly deployed on Tolkien’s stretch of the Western Front — as seen through medieval eyes.

|

A British tank at Thiepval on 25 September 1916, two days before Tolkien went back into the trenches there (Imperial War Museum) |

The story of Gondolin was soon joined by a whole cycle of “Lost Tales”, including a creation myth in which the world is shaped by music but ineradicably marred by a rebel angel and his harsh, repetitious discord. The story of the satanic Morgoth’s bid to conquer, pervert and destroy the world reads as a powerful indictment of the misuse of creativity.

Tolkien lost two of his closest friends during the Somme, and the Great War claimed the lives of about one in four of his wider circle — young men educated at public school and Oxbridge who typically ended up as junior officers at the sharp end.

Tolkien reworked his mythology over and over but never completed it. It was published posthumously as The Silmarillion. In the meantime, in 1937 he had begun a sequel to his successful fantasy yarn for children, The Hobbit. The Lord of the Rings reflected the darkening times and was set in the same world as The Silmarillion, but it springs to life because it describes Middle-earth – our world in a prehistoric era – through the eyes of hobbits. They represent ordinary people; more specifically, the weavers and labourers who formed the backbone of Tolkien’s Great War battalion, the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers.

Unlike the celebrated memoirists and poets of 1914-18, Tolkien wrote very little about what he saw in the trenches: but the images are there in the rotten and beautiful faces staring up out of the putrescent meres of the Dead Marshes; in the hobbit Merry crawling in the mud like a dazed animal to plant a knife in the back of his enemy’s knee; in Frodo and Sam, the officer and his batman, sitting in a blasted hole as the world erupts around them, wondering if their end has come.

|

|

This is the Great War not as tragic farce but as bitter personal endeavour. Robert Graves, eager to declare “Goodbye To All That” — to empire and deference and blind patriotism — forgot that the soldier on the Western Front could do anything except die piteously or go home wounded. Tolkien’s myth tells another truth about the war: soldiers in that horror were much more than passive victims. They were real people, resilient, cowardly, brutal and occasionally heroic.

If in two years’ time, in his third and final Lord of the Rings movie, director Peter Jackson sticks close enough to Tolkien’s narrative, we shall see the embattled city of Minas Tirith saved by the intervention, as if emerging from ancient legends, of a host of the dead: people who deserted their allies 3,000 years before, and have come at last to redeem their oath and to fight.

It is an astonishing, fantastical scenario, and morally striking: ghosts joining the war against evil. Yet how reminiscent of Memoirs Of An Infantry Officer, in which Siegfried Sassoon (pictured above) describes an exhausted infantry division returning from the Somme: “It was all in the day’s work … but for me it was as though I had watched an army of ghosts. It was as though I had seen the War as it might be envisioned by the mind of some epic poet a hundred years hence.”

© Evening Standard 2001. Reproduced with permission.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College