John Garth

Tolkien’s Middle-earth in its beginnings looked as different from the world of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion as an acorn does from an oak tree. In this extract from Tolkien and the Great War, I piece together how it stood just before he went off to fight in the Battle of the Somme in summer 1916 – even before The Book of Lost Tales which he began straight after the battle. Some details and spellings are familiar, many are not. Drawn from a handful of poems and from Tolkien’s first notebook of Elvish, it provides a fascinating snapshot of an astonishing imagination in its green youth.

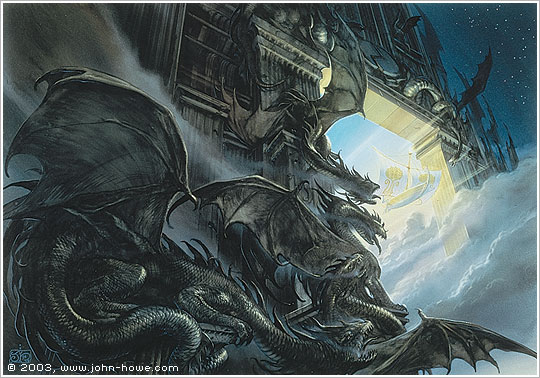

The Door of Night, by John Howe, showing the ship of the sun passing through what Tolkien, in his 1915 poem ‘The Happy Mariners’, called ‘Night’s dragon-headed doors’. © John Howe

The Door of Night, by John Howe, showing the ship of the sun passing through what Tolkien, in his 1915 poem ‘The Happy Mariners’, called ‘Night’s dragon-headed doors’. © John HoweEnu, whom men refer to as Ilūvatar the Heavenly Father, created the world and dwells outside it. But within the world dwell the ‘pagan gods’ or ainur, who with their attendants here are called the Valar or ‘happy folk’ (in the original sense of ‘blessed with good fortune’). Few of them are named: notably Makar the god of battle (also known as Ramandor, the shouter); and the Sūlimi of the winds; Ui, who is queen of the Oaritsi, the mermaids; and Niëliqi, a little girl whose laughter brings forth daffodils and whose tears are snowdrops. The home of the Valar is Valinor or ‘Asgard’, which lies at the feet of lofty, snow-capped Taniqetil at the western rim of the flat earth.

Beside Valinor is the rocky beach of Eldamar, once home of the elvish Eldar or Solosimpë, the beach-fays or shoreland-pipers. The royal house of the fairies, the Inweli, was headed by their ancient king, Inwë, and their capital was the white town of Kôr on the rocks of Eldamar. Now it is deserted: Inwë led the fairies dancing out into the world to teach song and holiness to mortal men. But the mission failed and the elves who remained in Aryador (Europe?) are reduced to a furtive ‘shadow-people’.

Mermaids: Arthur Rackham, 1919, for La Motte Fouqué’s Undine

Mermaids: Arthur Rackham, 1919, for La Motte Fouqué’s UndineThe Noldoli or gnomes, wisest of the faëry tribes, were led from their land of Noldomar to the Lonely Isle of Tol Eressëa (England) by the god Lirillo. The other fairies retreated from the hostile world to the island, which is now called Ingilnōrë after Inwe’s son Ingil (or Ingilmo). In Alalminórë (Warwickshire), the land of elms at the heart of the island, they built a new capital, Kortirion (Warwick). Here the goddess Erinti lives in a circle of elms, and she has a tower which the fairies guard. She came from Valinor with Lirillo and his brother Amillo to dwell on the isle among the elvish tribes in exile. Now the fairy pipers haunt the beaches and weedy sea-caves of the island. But one, Timpinen or Tinfang Warble, pipes in the woods.

The name Inwinórë, Faërie, was used by Tolkien for both Eldamar and Tol Eressëa. The elves are immortal and they drink a liquid called limpë (whereas the Valar drink miruvōrë). They are generally diminutive, some especially so: a mushroom is known as a ‘fairy canopy’, Nardi is a flower fairy, and likewise Tetillë, who lives in a poppy. Are such beings as these, or the sea-nymphs, akin to the ‘fairies’ who built Kôr? It is impossible to judge from the evidence of Qenya at this stage. Qenya is only one of several elvish languages; the lexicon also lists dozens of words in another, Gnomish.

‘The Fairy Ring’, by Victorian artist Walter Jenks Morgan. In Tolkien’s first Elvish lexicon, mushrooms were ‘fairy canopies’

‘The Fairy Ring’, by Victorian artist Walter Jenks Morgan. In Tolkien’s first Elvish lexicon, mushrooms were ‘fairy canopies’Sky-myths figure prominently side-by-side with the saga of the elvish exile to the Lonely Isle/England. Valinor is (or was?) lit by the Two Trees which bore the fruit of sun and moon. The Sun herself, Ur, issues from her white gates to sail in the sky, but this is the hunting ground of Silmo the Moon, from whom the Sun once fled by diving into the sea and wandering in the caverns of the mermaids.

Also hunted by the Moon is Eärendel, steersman of the morning or evening star. He was once a great mariner who sailed the oceans of the world in his ship Wingelot or Foamflower. On his final voyage he passed the Twilit Isles, with their tower of pearl, to reach Kôr, whence he sailed off the edge of the world into the skies; his earthly wife Voronwë is now Morwen (Jupiter), ‘daughter of the dark’. Other stars in Ilu, the slender airs beyond the earth, include the blue bee Nierninwa (Sirius), and here too are constellations such as Telimektar (Orion), the Swordsman of Heaven. The Moon is also thought of as the crystalline palace of the Moon King Uolë·mi·Kūmë, who once traded his riches for a bowl of cold Norwich pudding after falling to earth.

Besides wonders, there are monsters in these pages too: Tevildo the hateful, prince of cats, and Ungwë·Tuita, the Spider of Night, whose webs in dark Ruamōrë Earendel once narrowly escaped. Fentor, lord of dragons, was slain by Ingilmo or by the hero Turambar, who had a mighty sword called Sangahyando or ‘cleaver of throngs’ (and is compared to Sigurðr of Norse myth). But there are other perilous creatures: Angaino (‘tormentor’) is the name of a giant, while ork means ‘monster, ogre, demon’. Raukë also means ‘demon’ and fandor ‘monster’.

The fairies know of Christian tradition with its saints, martyrs, monks and nuns; they have words for ‘grace’ and ‘blessed’, and mystic names for the Trinity. The spirits of mortal men wander outside Valinor in the region of Habbanan, which in the abstract is perhaps manimuinë, Purgatory. But there are various names for hell (Mandos, Eremandos and Angamandos) and also Utumna, the lower regions of darkness. The souls of the blessed dwell in iluindo beyond the stars.

It is curious — especially in contrast to his later, famous writings — that Tolkien’s own life is directly mythologised in these early conceptions. He left his discreet signature on his art, and at times the lexicon is a roman à clef.

The Lonely Isle’s only named locations are those important to him when he began work on it: Warwick, Warwickshire, Exeter (Estirin) College and Oxford (Taruktarna). Possibly we see John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and his beloved Edith in Eärendel and Voronwë, but Edith is also certainly represented by Erinti, the goddess who presides aptly over ‘love, music, beauty and purity’ and lives in Warwick – where Tolkien and Edith Bratt married on 22 March 1916. Amillo equates to Hilary, Tolkien's younger brother. John Ronald was perhaps declaring his own literary ambitions as Lirillo, god of song, also called Noldorin because he brought the Noldoli back to Tol Eressëa. [See note below.] Tolkien’s writings, he may have been hinting, would signal a renaissance for Faërie.

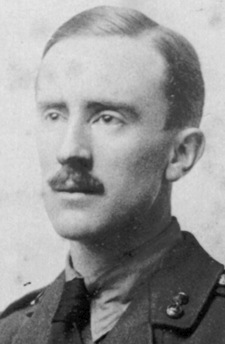

Tolkien in army uniform in 1916, when Middle-earth was brewing

Tolkien in army uniform in 1916, when Middle-earth was brewing

War also intrudes. Makar the battle god seems to have been one of the first named Valar (and Melko, later Melkor Morgoth, does not yet appear)... Particularly striking is how Qenya at this stage equates Germans with barbarity. Kalimban is ‘“Barbary”, Germany’; kalimbarië is ‘barbarity’, kalimbo is ‘a savage, uncivilized man, barbarian. — giant, monster, troll’, and kalimbardi is glossed ‘the Germans’.

There is a strong sense of disillusionment in these definitions, so devoid of the attraction which Tolkien had felt towards ‘the “Germanic” ideal’ as an undergraduate (Letters 55). He lived in a country wracked with fear, grief and hatred, and by now people he knew had been killed by Germans. Yet this equation of Germany with barbarism did not survive his encounters with German soldiers on the Somme. Tolkien later insisted there was no parallel between the Goblins he invented and the Germans he had fought, declaring, ‘I’ve never had those sort of feelings about the Germans. I’m very anti that kind of thing.’

Notes

Names and their significances differ from the later legendarium: for example, Enu (God), which Tolkien relates to a Qenya verb meaning ‘devise’, was ultimately renamed Eru, translated as ‘the One’. Some names eventually found an entirely different use: decades later, Sangahyando was given to a rebel royal of Gondor in The Lord of the Rings. Some concepts, such as the Valar and Eldamar, were to undergo many further developments. Tolkien’s use of diacritical accents changed too, so Ilūvatar became Ilúvatar.

Erinti, Amillo and Lirillo: February, the month of Hilary Tolkien’s birth, is named Amillion after Amillo; but Tolkien had to split January in two so he could name half Erintion, in honour of Edith’s birthday (21 January) and the other half Lirillion, in honour of his own (3 January). See Christopher Gilson, ‘Narqelion and the Early Lexicons’, Vinyar Tengwar 40, p. 9.

This reconstruction is based primarily on the Qenya lexicon (Parma Eldalamberon 12: Qenyaqetsa: The Qenya Phonology and Lexicon, ed. Christopher Gilson, Carl F. Hostetter, Patrick H. Wynne, Arden R. Smith), along with the available poetry of 1915, and notes on Eärendel’s Atlantic wanderings and ‘The Shores of Faëry’ (The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, pp. 261-2; internal evidence suggests that other outlines, p. 253ff., were written later). Tolkien is unlikely to have risked taking the lexicon on active service, and its state circa March 1916 may be broadly surmised by excluding all entries lacking in ‘The Poetic and Mythologic Words of Eldarissa’, a list copied from it probably soon after he returned to England (Parma Eldalamberon 12, pp. xvii-xxi). Some details appearing only in that list are assumed to postdate the initial lexicon phase, and omitted here. The reconstruction takes no account of unpublished poems, notes or outlines, and covers a period (beginning in early 1915) in which conceptions were probably very fluid.

The poems considered here are published in the two volumes of The Book of Lost Tales, except ‘The Tides", which appears in The Shaping of Middle-earth. All are discussed in Tolkien and the Great War. Roughly chronologically, they are ‘The Voyage of Éarendel the Evening Star’ (September 1914, shortly after the outbreak of war); ‘The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon’ (March 1915); ‘You and I and the Cottage of Lost Play’, ‘Goblin Feet’, ‘Tinfang Warble’ and ‘Kôr’ (all April 1915, as Tolkien neared the end of his student life); ‘The Shores of Faëry’ (the first time long-standing elements appeared in place with Elvish names) and ‘The Happy Mariners’, both from July 1915, as Tolkien joined the British Army; ‘A Song of Aryador’ (September 1915); ‘Kortirion among the Trees’ (November 1915); ‘Narqelion’ (November 1915/March 1916), which is in Qenya and is analysed by Christopher Gilson in Vinyar Tengwar 40; ‘Over Old Hills and Far Away’ (December 1915/February 1916); and ‘Habbanan beneath the Stars’ (December 1915). The last poem from the period to have been published is the extremely interesting, partly autobiographical ‘The Wanderer's Allegiance’ (March 1916), of which part was imported into the mythology in 1917 – but that falls outside the scope of this reconstruction of Tolkien's mythology as it stood in early 1916.

For this webpage I have omitted a passage on words related to war, which includes items probably postdating the Somme; I have added some extra contextual detail , and from elsewhere in Tolkien and the Great War I have brought in two important points about the development of Tolkien's mythology: that his monstering of the Germans seems to have stopped with the Battle of the Somme, and that Melko does not seem to have appeared until after the Somme. As of 14 April 2014, I have corrected some diacritics which had inadvertently appeared in the website version; my thanks to Magradhaid of LotR Plaza and Troels Forchhammer for alerting me to these errors.

Text © John Garth 2003, 2013. All quotations from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien © The Tolkien Trust / The J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust 2003. The later quotation about the Germans comes from an interview with Philip Norman in the Sunday Times Magazine, 15 January 1967. ‘The Door of Night’ is reproduced with permission of John Howe.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College